At a recent conference hosted by the California Part Time Faculty Association (CPFA), a variety of speakers laid out the current situation in stark and sometimes shocking terms.

Stark Inequalities in Pay and Working Conditions

David Milroy, Executive Director of CPFA gave a talk entitled “Where Does the Money Go? Analysis of North Orange County Community College District (NOCCCD) Salaries”.

Using the information posted at www.transparentcalifornia.com (which reports where all state money/salaries are going, including higher education) Milroy pointed out some glaring inequalities in the system.

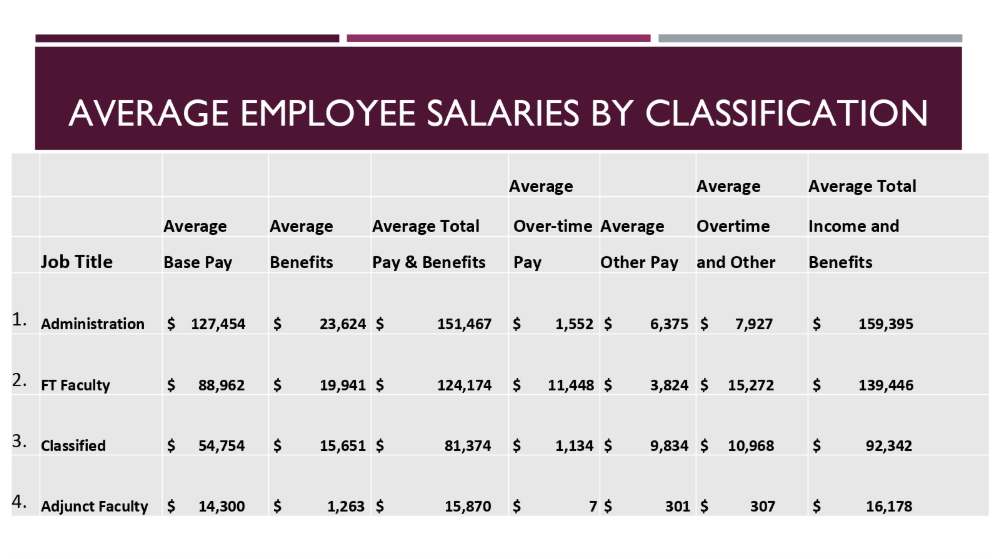

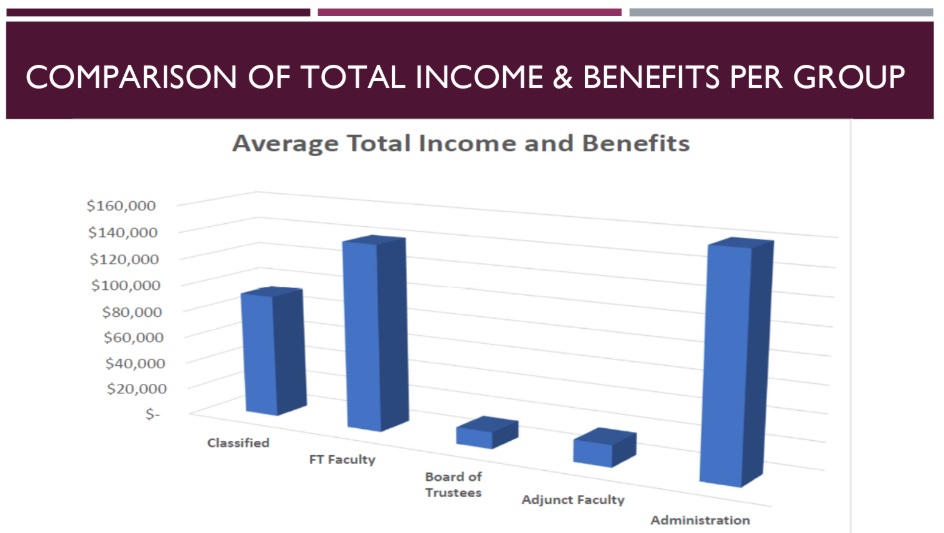

He showed slides comparing average pay between administration, full-time professors (faculty), classified (non-teaching) employees, and part-time professors. According to the chart below, the average administrator in this district makes $159,395 (including benefits), average full-time faculty member makes $139,449 (with benefits), average classified employee makes $92,342 (with benefits), and at the bottom of the pay scale, part time professors make an average of $16,178.

Now, one might argue that part-time professors work fewer hours than full-time faculty. Most districts have limitations on the number of units part-time professors are allowed to teach. So, to get a better understanding of “pay parity” we must compare the hourly pay. Even though full-time professors are paid a salary, it is possible to determine their hourly pay by looking at the number of hours they are required to work (in their employment contracts), and divide that by their total pay. Using this information—part-time faculty are paid approximately 50% of the hourly rate of full-time professors in the NOCCCD. This is similar to other community college districts, and across the CSU system.

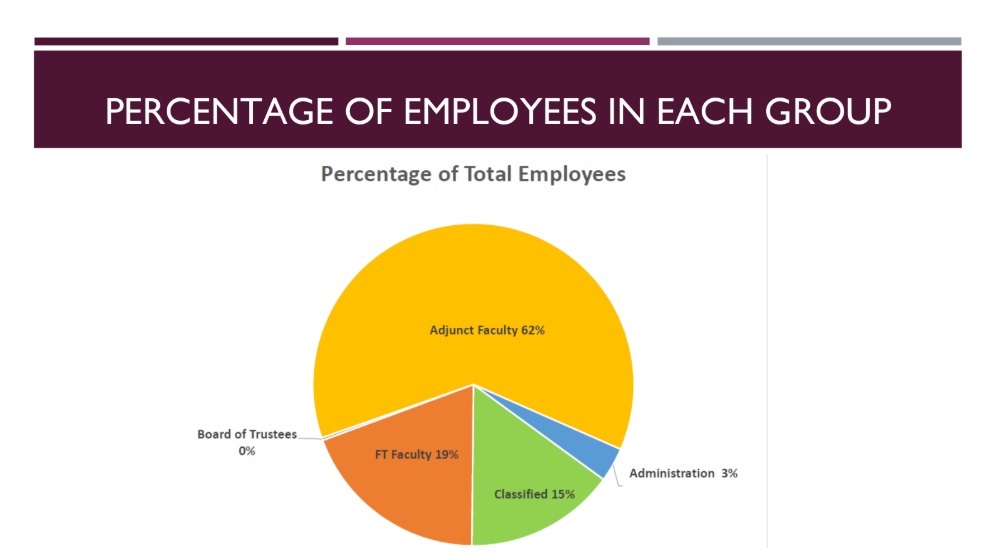

Milroy further showed that there are far more part-time professors than full-time professors, so the colleges and universities are saving a lot of money by having underpaid part-timers teach the lion’s share of the classes.

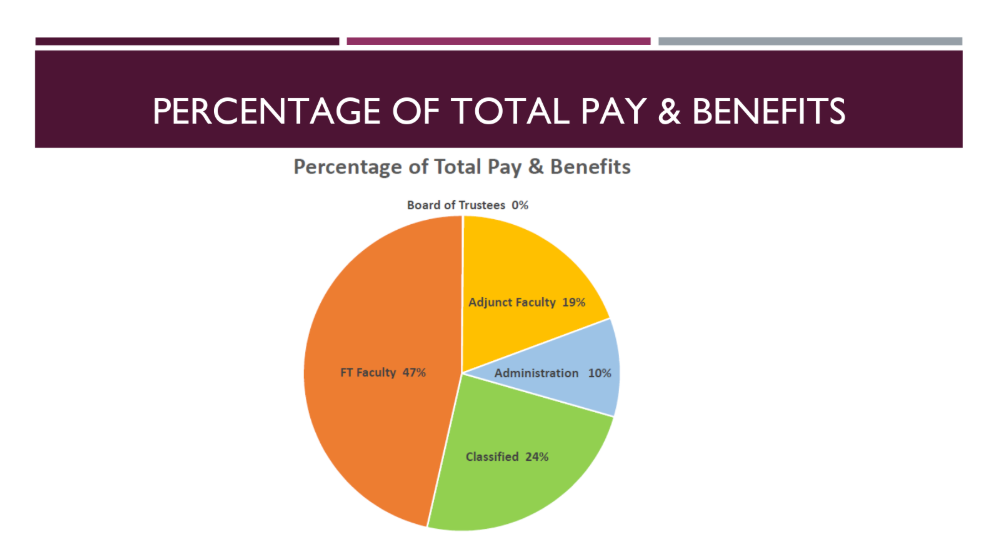

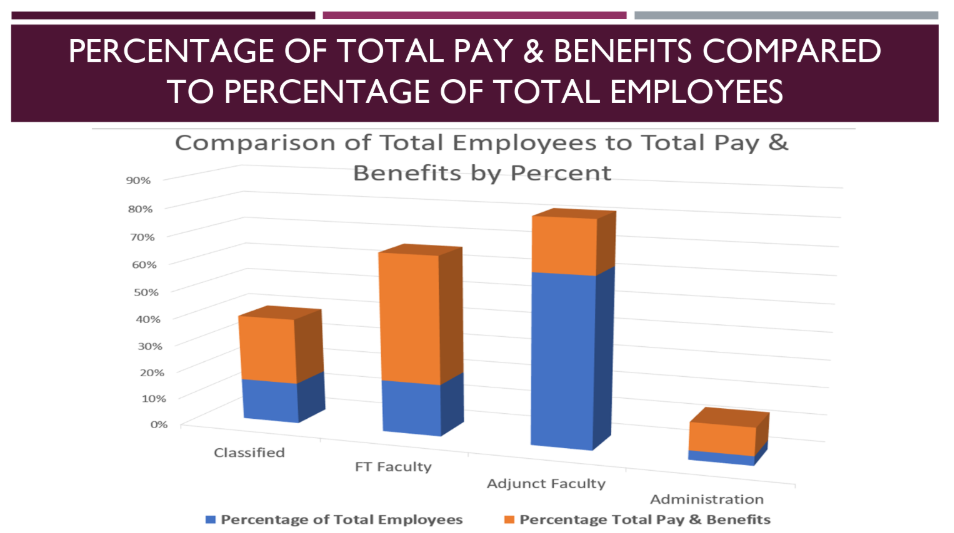

To highlight the inequality of pay compared to number of employees, Milroy showed that, despite the fact that part-time faculty makeup 62% of the total number of employees, they only get 19% of the total stare of pay. Full-time faculty, who make up a numerically lower percentage of employees (19%), get 47% of the allocated pay.

Viewed another way, on the graph below, we see again that while adjuncts make up the largest percentage of employees, their share of pay is highly disproportionate to their full-time counterparts.

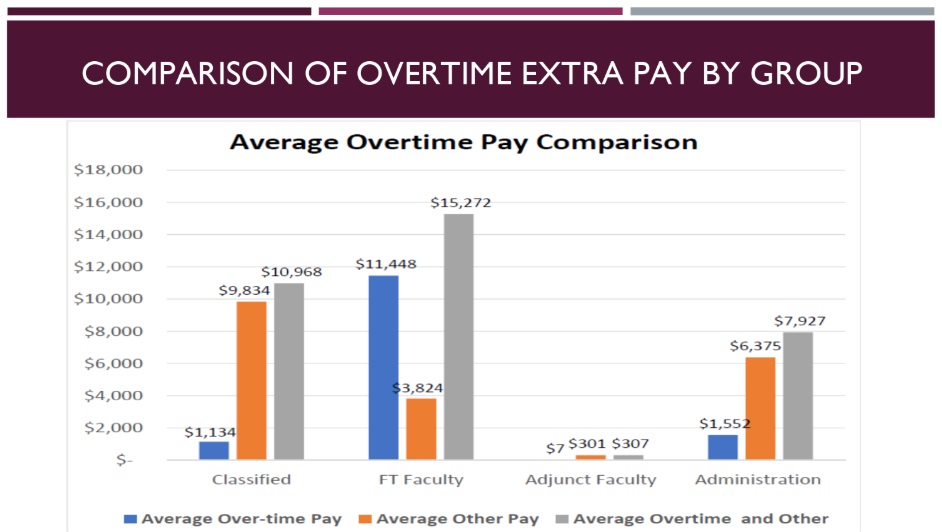

Add onto this disparity the fact that full-time faculty get a lot of overtime pay, while part-time faculty get virtually none.

And here’s another chart comparing the total average income

and benefits per group, which highlights the above-mentioned disparities.

While Milroy focused on the North Orange County Community College District, he said, “If you do this for any community college in the state, they’ll come out pretty close to this. Usually, there are about three times as many adjunct (part-time) as full-timers.”

When you add this pay disparity to other aspects of working conditions for part-time faculty (lack of similar health benefits, little job security, lack of office hours, etc.) the picture becomes quite shocking.

“Adjunct faculty are the largest employee group in any college and they do not deserve the ‘left-overs’ after all other employees have had their fill,” Milroy said, “Why should 62% of the employees who bring in more than half the state funds by teaching more than half of the classes be paid only 19% of the budget? Obviously, there is money in the district—it just mainly goes to the top 22% of employees who get 57% of the budget.”

How Did We Get Here? A Brief History of Part-Time Faculty in California

Given these shocking and systematic inequalities in the system, one might ask, “How did we get here?”

To answer this question, Evan Hawkins, executive director of the Faculty Association of California Community Colleges (FACCC), gave a brief history of part-time faculty in California.

Up through the 1960s, there were only full-time faculty at California’s colleges, so there was not originally a two-tiered system (full-time and part-time).

Starting in the late 1960s, there was a demand for part-time employment overall in the workforce. By the 1970s, the Board of Governors concluded that no more than 25% of instruction should be taught by part-time faculty—who were mainly teaching supplemental night and weekend classes.

And then came the watershed moment that jump-started this whole mess. In 1978, Proposition 13 (which placed limitations on property taxes) created revenue losses in higher education that led to the “need” for more part-time faculty to fill the funding gap.

“Prop 13 was a game-changer in the way colleges were financed and changed so many different things,” Hawkins said, “You can look at that moment in time and see a lot of the challenges that we have today essentially coming from there…after Prop 13 you start seeing more of the reliance on part-time faculty because of the drop in revenues that colleges are receiving.”

In the 2000s, a recession led to more cuts to higher education. When there’s a recession, there’s more part-time faculty, because they are cheaper. We now have a situation where it’s normal to have nearly two thirds of college classes being taught by part-time professors (who, incidentally, often have the same education and qualifications of their full-time colleagues).

Evan Hawkins, executive director of Faculty Association of California Community Colleges

What Can Be Done?

Various panelists at the CPFA conference gave information and ideas about what can be done to address this glaring inequity at the heart of our higher education system.

Both CPFA and FACCC work with faculty unions and legislators to support bills that aim to improve the working conditions of part-time faculty.

Hawkins mentioned a few bills currently making their way though the California legislature, which deal with part-time faculty, such as Assembly Bill 897, which would increase the maximum time a part time, temporary employee may teach, without becoming a contract employee, to 85% of the hours per week of a full-time employee having comparable duties.

This bill has been debated among faculty advocates, with some arguing that it would actually increase the levels of exploitation. However, while the bill would do nothing to address the problem of pay inequality, it would perhaps help with another common problem faced by part-time faculty—the fact that they often teach at multiple colleges to cobble together a livable wage. If they could teach at one, instead of three colleges, their working conditions would likely be improved.

One way that faculty can be more informed and involved is by joining organizations like CPFA, FACCC, and (for those who teach in the NOCCCD, Adjunct Faculty United), which send out regular updates to members, and organize opportunities for part-time faculty to be involved in decision-making processes.

“It’s really about allowing your voice to be heard. Your legislators should know you. You should be talking with them regularly. Visit their district offices that they have down here,” Hawkins said. “If there’s one thing you can take away from what I’m saying today is to call the district office of your senator or assembly member and set up a time just to talk with them and share your story about what it’s like to be a community college part-time faculty member…I promise you, if all 40,000 part-time faculty told their stories, it would make a difference.”

Adam Wetsman, current president of FACCC, said that part-time faculty need to get involved in as many places as they possibly can: in the union, on the Academic Senate, and in department meetings. Part time faculty should be seen everywhere so that people say, “Ah, yes. These issues are very important for all of us here.”

One challenge to this is that, unlike full-time faculty, part-time faculty are generally not paid to get involved in their departments or with the college administration. Additionally, part-time faculty are are underrepresented in state teachers unions. NOCCCD is unique in that it has a union for part-time faculty, Adjunct Faculty United.

Adam Wetsman, FACCC President

Wetsman said that social media can be useful in helping the public to understand the plight of part-time faculty. He showed a Facebook post from a part-time faculty (aka contingent) member at Ithaca College in New York which said, “I am an IC contingent faculty member. I am on Medicaid.”

“Have media campaigns that tell individual stories of adjunct faculty member’s real experiences and issues.” Wetsman said. “These things humanize the issue and really show the plight of the 40,000 people who are providing education to over 2 million people across the state. Make it personal, show the struggles that part-time faculty are going through in order to help students improve their lives and be more successful.”

Wetsman pointed out that the situation in California is not unique—this is a nationwide problem.

“It is a drug to rely on cheaper labor and to exploit that cheaper labor,” Wetsman said. “To get out of that spiral is going to take a momentous effort. It’s going to take a change across the board.”