Decades of decisions

California’s community college system, formally established in 1967, grew out of junior colleges across the state that date to 1910. Employing a majority of full-time, tenured faculty “engaging with students consistently” was the original goal, Graves said.

Like other public institutions, the districts “were not immune to the economic hardship that’s been brought throughout the years,” he said. “One of the biggest expenses is personnel. Faculty tenured positions are very expensive. When you cut those lines, you get that increase in part-time faculty.”

Both the Vietnam War and California’s Proposition 13 anti-tax revolt in 1978 impacted the system greatly, Berry said.

The anti-war and social movements of the ’60s led to people going to “college who wouldn’t have been in college before,” including returning veterans, he said. The demand exceeded the system’s capabilities, and the autonomy of locally-controlled districts left the fixes to the whims of individual district administrators.

“A collection of little decisions made by hiring officials at various levels of the community colleges to solve immediate problems” led to the steady growth in the use of adjuncts, Berry said.

The steep cuts dictated by Proposition 13 rippled through California’s K-12 system, resulting in more students getting to community college behind in basic skills and needing remedial courses, Berry said.

“The schools were worse. So, there was a greater need for remediation. And the community colleges had to put on all of these remedial courses.” That required more faculty at a time of unstable funding. Adjuncts were cheaper.

Prior to Proposition 13, college districts raised roughly 80% of their budgets through property taxes. The state took over funding because of the freeze on tax assessments that the proposition created, but the new system caused inequalities between the districts.

It took the state until 2006 to enact a new funding formula pushed by then Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger, a former community college student. It was 28 years after Proposition 13, and adjuncts had long dominated the teaching ranks.

Oddities of the academic workforce

The use of adjuncts is a byproduct of the open enrollment of community colleges, Garcia, of the University of Texas said. “We accept all. There’s no limitation to the number of students that are going to be accepted like at a university.

“That means that there is a need to have more faculty,” she said. Adjuncts are cheaper. “There are always concerns for the budget.”

In 1998, Scroggins, then a chemistry professor, was president of the statewide community college senate, wrote a position paper entitled “Overuse and Undercompensation of Part-Time Faculty in the California Community Colleges.”

The system “paid part-time faculty low wages based only on classroom hours encourages colleges to overuse part-time faculty to balance their budgets,” he wrote 24 years ago, complaints that continue today.

But as a district president, he told EdSource recently, he now sees the situation “through a different lens.”

He has to make decisions that affect how adjuncts are deployed “but with criteria about operating the entire college, rather than representing the faculty and looking at it from the experience of a faculty member,” he said.

Full-time faculty “give me a stable workforce,” he said. But “the realities haven’t changed surrounding adjuncts.”

There are “oddities about the way higher education handles its major workforce,” he said. Colleges “produce their outcome that is educated students by a workforce that consists primarily of faculty overseen by managers.”

Higher education’s “in some ways an industry. It runs by economic rules. You control both the compensation and the number of employees you have by how successful you are in the market,” he said, referring to enrollment.

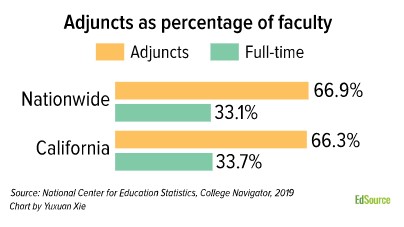

At systems like the California community colleges, tenured faculty, serving in high positions such as department chairs, are primarily the managers. Adjuncts are primarily the workforce.

When the pandemic forced students to drop out starting in 2020, “I didn’t have students to teach,” Scroggins said. “So, I had to reduce my workforce, and I wasn’t going to lay off the most productive faculty,” he said, referring to full-time faculty, who generally teach five classes a semester.

It was adjuncts, units of flexibility, that didn’t get teaching assignments.

A zero-person department

The stress of worrying about if and when work will come can be a constant presence in an adjunct’s life, said Linda Sneed, a part-time English instructor at Sacramento-based Los Rios District and member of the local union’s executive board.

Underlying that, she added, is the dismissive way adjuncts are often treated despite the fact the system can’t operate without them.

Sneed attended a faculty meeting a few years ago when a presenter used a strange term – “a zero-person department.” She said she thought that might mean departments where there was no one to teach classes. She raised her hand for an explanation.

“A zero-person department is a department where there are no classes being taught by full-time faculty,” she was told. “The classes are being taught by adjunct faculty.”

Sneed recalled making eye contact with other adjuncts. There was nervous laughter. She hoped the reaction would stop the use of dehumanizing phrases about part-timers.

But during a meeting in January, she said, a full-time faculty member referred to himself as “a one-person department,” then added that he had an adjunct too.

“It’s disturbing that this has persisted,” Sneed said.

“We’re really invisible.”

Daniel J. Willis, EdSource data journalist, contributed to this investigation.

Andrew Reed, EdSource staffer, and Raya Torres, a journalism student at CSU Long Beach and a member of EdSource’s California Journalism Corps, contributed to this story.

I teach at Evergreen Valley College. Did the college not divulge their average salaries for adjuncts?

Fyi, Adjuncts in Noncredit departments make approximately 30% less than Adjuncts in Credit departments. Meanwhile the state is paying more Into the Noncredit department. Where is the equity in this? We teach the most at risk students while holding the same educational designation and providing quality learning opportunities.